Cultural accountability: what is it and how does it work in 2020?

In 2019, Marlee and Keely Silva, sisters of Kamilaroi/Dunghutti descent, created the Instagram account ‘Tiddas4Tiddas’ with the aim of showcasing positive stories of First Nations women across the country.

Inspired by the 2018 NAIDOC theme ‘because of her we can’, the account was an immediate success, gaining a large following.

Following the success of the Instagram account, the sisters launched a podcast and Marlee signed a book deal. Marlee received significant mainstream media attention promoting her growing ‘Tiddas 4 Tiddas’ media business which was described as “clickable empowerment”, and “a grassroots movement sharing the untold stories of powerful Indigenous women”.

With these brilliant beginnings and good intentions, it is hard to understand why after weeks of building criticism from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women on Instagram, the sisters decided to delete the account.

This event sparked a whirl of conversations in the wider community, leaving a lot of confusion.

These conversations were centred around whether the criticism they received was legitimate cultural accountability or something else – such as tall poppy syndrome, lateral violence or just plain ole’ jealousy.

The rise and fall of the ‘Tiddas4Tiddas’ Instagram account offers a unique case study through which to understand and assess cultural accountability in the contemporary context.

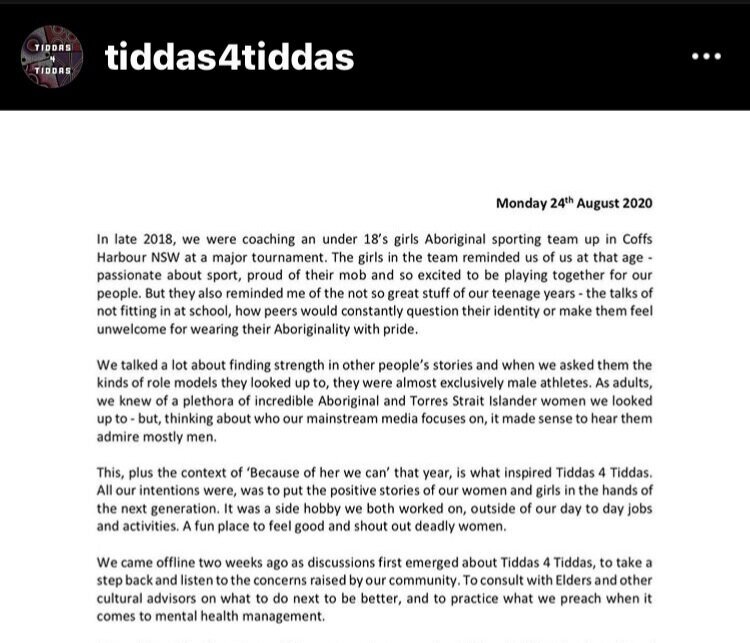

Tiddas 4 Tiddas Statement

What were the criticisms?

As the page developed, what started to become very evident to other women in the community, was that the stories being told were only one type. Those typically successful in the eyes of white Australia – university educated, employed, the ‘black kid makes good’ architype.

But this isn’t real – it’s just a shiny, plastic version of our community. Where was the diversity?

The problem is that Tiddas4Tiddas perpetuated the assimilationist narrative that Aboriginal people and communities should be celebrated if they aspire to, and attain, white middle-class values.

But black women should be valued, admired, and empowered whether they can be considered ‘successful’ by white society or not.

Further, the community wanted to know why they didn’t use their platform to educate their followers and advocate for change. In particular, the community was frustrated that the sisters failed to use their platform to address or even discuss the issues of over policing in our community, police brutality and deaths in custody.

These are pressing and urgent issues for our mob because they affect our families and our daily lives.

Some people felt that the Silva sisters were using the images and intellectual property of black women to create a white-washed “Indigenous” brand which would be commercially palatable, but would not be a platform to address issues that would be uncomfortable for a white audience.

In addition to this, issues of content ownership were raised. Allegedly, once content was posted on Instagram, the words and images of black women became the intellectual property of this international social-media platform. It is still unclear what the business arrangement for this was.

Now I bet a lot of you are saying: “Well, yeah. That’s how copyright law works.” But that’s a very white way of understanding ownership and there are lots of ways in which copyright can remain with the creators or authors of work.

According to the Australia Council for the Arts’ ‘Protocols for Using First Nations Cultural and Intellectual Property in the Arts’, a key principle underpinning all aspects of engagement with Indigenous people, communities and their cultural and intellectual property is their right to own, protect, maintain, control and benefit from their cultural heritage.

In practice this could look like structuring an organisation or business to act ethically by diverting a portion of the profits back into the community, for example. If you profit from the community, you should also give back to it.

Thirdly, the sisters were getting recognition in the mainstream media for the work they were doing. This is great and well deserved. There is nothing wrong with building a business off the ‘black experience’, but their lack of accountability to the community raised questions around privilege, access and cultural appropriation.

The black community cried out for authenticity and accountability. This cry seemed to fall on deaf ears.

Rather than responding to a call for an open and honest dialogue about cultural accountability, colourism and inter-sectional representation, the sisters blocked and ignored their detractors, most of whom were First Nations women.

In an open letter posted on Instagram in August this year, the sisters said:

“Vicious, harmful, unproductive and in many cases, false comments about our identity and integrity, have had an immense impact on our psychological well-being, and in the case of such false comments, we have been forced to put these matters in the hands of our lawyers”.

Tiddas 4 Tiddas - Media Statement Screenshot

The letter’s tone of indignant denial frames the sisters as victims, which is a common tactic used by those with proximity to whiteness to avoid accountability. They defended their behaviour and suggested those with concerns were out of bounds and attacking them because they were white-passing.

(I won’t go into more detail about this issue here as several books can be written on this topic, but I encourage you to research this topic further for yourself.)

While I understand how the communities’ criticism could be perceived as an unfair attack on nice young women who were doing good, I am of the opinion this event demonstrated the consequences of not following protocols of cultural accountability.

It also demonstrates how a lack of cultural accountability can be destructive and harmful in many contexts in which First Nations people interact.

Aboriginal social structures

Before we can understand cultural accountability, we must understand Aboriginal social structures. Full disclosure – I am speaking in very general terms about Aboriginal communities. There are too many details and intricacies to describe in detail and each group will have their own definitions of this.

Cultural accountability stems from our (Goorie/Koorie /Murrie) social frameworks and cultural practices. These are referred to as kinship systems and customary law or lore.

Without going into an in-depth discussion. In its simplest definition, First Nations social structures are relational. This means understanding your position within the community. We often ask questions such as “who are you?”, “where are you from?” and “who’s your mob?”, to understand this position.

But understanding your position is more than self-identification. It’s understanding who you are to people within the community, what your role is and whether you have the authority to do and say things on behalf of the community, your family or just yourself.

It is about understanding your cultural obligations to each other. It’s looking out for those less fortunate - feeding them, housing them, sharing your resources. It’s taking responsibility for those younger than you, showing them right from wrong. It’s looking after Country, places of significance, ensuring abundance for generations to come and not just thinking about the short term.

Cultural obligations are also things you should not do. Such as not disclosing sacred information to those who should not know that information.

We should follow cultural governance structures which give authority to certain people to make certain decisions. When we use our Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, it is right to first speak to those with the authority over that and include our community in the decision-making process.

With cultural obligation comes cultural accountability. But we will get to this later on.

Understanding the impact of colonisation

Layered on top of these practices of cultural accountability, community governance and lore, are colonial traumas and their repercussions.

They include genocide, dispossession, removal of children, western dominance in education, assimilation and cultural erasure which leads to things such as lying about your identity in order to survive, not knowing who you are, fragmented families and communities, loss of knowledge, customs and language, disconnection from country and community and the list goes on.

Broken accountability

Now if you have a disagreement with someone you know, you would try to have a discussion with them first, right? Sure, it’s hard but it’s your obligation to let them know what they’ve done is wrong.

Within the Aboriginal community context, those with the privilege of knowledge have an obligation to let those who don’t know what the right way is.

If they fail to listen to you, you would get someone with more authority in the community to say something to them.

Now this is when things get tricky – our community is displaced and divided. A lot of mob don’t live on their country or are not connected to community as such. So how do they stay accountable?

Another issue which arises is that communities have, and continue to, suffer severe hardships. As a result, they have lost those customs of accountability or those structures are no longer functioning properly. Even more tragically, those who had the authority to step in or hold people to account have sadly passed on in some instances.

So now you can see, we have a real problem.

Understanding privilege

You don’t need to be poor or suffering to be an authentic Aboriginal person, but not recognising your privilege becomes a problem when you decide to speak for the community.

As a community, we have moved beyond one-dimensional understandings of indigeneity or what it means to be a First Nations community member. Let’s talk about this. Let’s not pretend it doesn’t exist.

I am privileged because I come from a strong, connected line of ancestors. Yes, my family suffered. They were removed from their country. They were told how to live, but I know who I am. This is a privilege many others do not have.

I am privileged because I had a stable family environment growing up. I had food everyday and a bed to sleep in.

I am privileged because my parents could afford to send me to a private school. I’m privileged because I had the opportunity to go to university and now have a well-paying job.

I am priviledged because I am a cis-straight women.

All this privilege does not take away from my identity as an Aboriginal woman, or my connection to culture and land.

However, I must recognise it and how the intersections between systemic racism and intergenerational poverty impacts most of our community. I must do this in my thinking, in reflecing on my experience, in my practice as a story-teller and in my work. I do this by listening to my community.

I am accountable to them and I should be.

Why it’s not lateral violence

Lateral violence occurs when people of the same community retaliate against each other, instead of their actual enemies. Examples include exclusion for social groups, not being promoted at work, bullying, etc.

You can see how the feedback, questions and commentary could be seen to be lateral violence, I know I certainly did.

When I first noticed things were flaring up on this social media, I originally felt sorry for them. I thought “just leave them alone, they’re not hurting anyone.” I also believed the account was creating a platform for much needed diversity and representation in both the media and community more broadly.

I thought publicly calling them out would do more harm than good and could cause some significant wellbeing issues for the sisters. I also felt scared to call them out when I didn’t have a resolution or a way forward.

But then the more I heard about the quiet words, the private messages, the requests for meetings, the more I became concerned.

Why? Because pulling people up, trying to steer them back onto the right path is all part of Aboriginal cultural accountability.

As said earlier, those with knowledge have an obligation to show those without, the right way. This is part of our cultural obligation. I know that if I do or say something wrong or not in the best interest of my community, I will be held accountable.

My family, my sister girls, my friends and people I know in the community will pull me up. This has happened to me, and to most Aboriginal people I know. It is often delivered with tough words in a harsh tone. It is sometimes hard to process this feedback, but it has always helped me to learn.

I can discern the difference between lateral violence and cultural accountability because one has my best interests at its heart. Guess which one?

So as things escalated and they continued to defend their behaviour, instead of addressing community concerns, it became evident to me that what was going on was not lateral violence.

Was there a resolution?

The archived tiddas4tiddas account.

There has been no real resolution. The T4T platofrm has been disabled and who know’s if it will be revived.

I still believe there is a way back to redemption and inclusion in the community. It takes humility and a willingness to learn.

That is something I love about our community. If you come with the right intention, you will be met with the right intention. So now it’s really up to them.

I hope they can find their way back home.

Note: Tiddas4Tiddas were contacted for comment and were not prepared to make a statement at this time.